Navigation Menu

Contact Us

- Email:

- info@wxavatar.com

- Address:

- Yurong Village, Yuqi Street, Huishan District, Wuxi, China.

Release Date:Mar 31, 2025 Visit:75 Source:Roll Forming Machine Factory

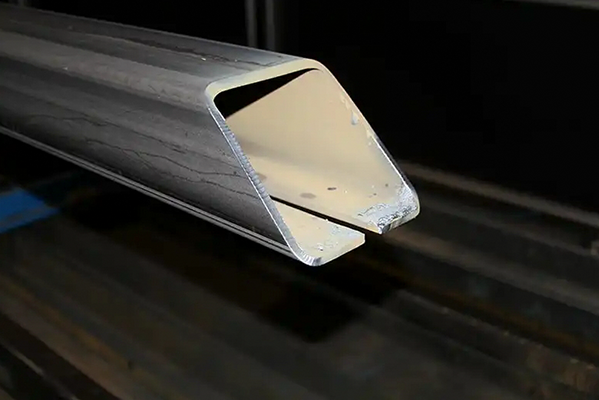

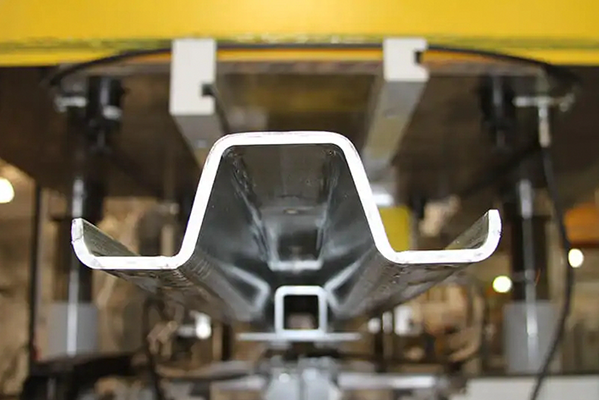

Thick gauge roll forming production lines are powerful for shaping heavy-duty metal profiles, but they come with several disadvantages that can impact efficiency, cost, and flexibility. Here’s a breakdown of key drawbacks:

1. High Capital and Operational Costs

Expensive Machinery: Heavy-duty rollers, reinforced frames, and high-power motors required to handle thick materials increase upfront investment.

Tooling Costs: Custom dies and rollers for thick gauges are costly to design, manufacture, and maintain.

Energy Consumption: Greater force and power are needed to form thick metal, leading to higher electricity costs.

2. Limited Flexibility

Material Constraints: Best suited for specific metals (e.g., structural steel). Brittle or ultra-hard alloys may crack during forming.

Profile Complexity: Thick materials are harder to bend into intricate shapes, limiting design options compared to thin-gauge forming.

Slow Changeovers: Switching between profiles or thicknesses requires time-consuming adjustments to rollers and tooling.

3. Production Speed and Efficiency

Slower Throughput: Forming thick metal requires slower line speeds to avoid defects like cracking or misalignment.

Material Waste: Higher scrap rates due to trial-and-error adjustments, edge trimming, or setup errors.

4. Maintenance and Downtime

Frequent Wear and Tear: Components like rollers, bearings, and shafts degrade faster under the stress of thick-gauge forming, increasing maintenance frequency.

Complex Repairs: Replacing heavy-duty parts is labor-intensive and may require specialized technicians.

5. Floor Space and Infrastructure

Large Footprint: Heavy machinery and support systems (e.g., cranes, cooling units) demand significant factory space.

Reinforced Foundations: Floors must withstand the weight and vibrations of thick-gauge equipment.

6. Skill and Labor Requirements

Specialized Operators: Skilled technicians are needed to manage setup, alignment, and troubleshooting.

Training Costs: Operators require extensive training to handle safety risks and process intricacies.

7. Market and Application Limitations

Niche Applications: Thick-gauge forming is primarily used for structural components (e.g., beams, rails), limiting its use in industries requiring lightweight or delicate profiles.

Competition from Alternatives: Processes like extrusion, forging, or welding may be more cost-effective for certain thick-metal applications.

8. Environmental and Regulatory Challenges

High Carbon Footprint: Increased energy use and material waste contribute to environmental impact.

Noise and Emissions: Loud operations and metal particulates may require additional compliance with workplace safety regulations.

Mitigation Strategies

Automation: Use automated material handling and sensors to reduce waste and labor costs.

Predictive Maintenance: Monitor equipment health to preempt failures.

Hybrid Processes: Combine roll forming with secondary operations (e.g., welding) to expand product capabilities.

Conclusion

While thick gauge roll forming excels in producing durable, high-strength metal profiles, its disadvantages—high costs, limited flexibility, and maintenance demands—make it less suitable for industries prioritizing speed, complexity, or cost efficiency. Careful ROI analysis and process optimization are essential to justify its use.